On the Love of Art: Fake, Forged or Authentic

- Noa Ishaki

- Feb 18, 2016

- 8 min read

This past week I went to a presentation at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM)—all thanks to my friend Jody—called Deceived: A Closer Look at Art Fakes and Forgeries with Kevin Ray, Esq. The topic is especially hot lately because of the recent Knoedler Gallery trial settlement. I thoroughly enjoyed it and learned a lot about art fakes and forgeries throughout history, and got to think a lot about the subject too.

What is so fascinating about reading or watching movies about art forgeries, heists, bank robberies and such? Is it because there is the element of danger and glamour at the same time? I am not sure. I mean, why do we like crime novels and films for that matter? Well, before I contemplate on this issue any further, here are some of the details of the Knoedler Gallery case:

Knoedler Gallery at 19 East 70th Street

Photo: artinfo

The Knoedler & Company was one of the oldest art galleries in New York established in1846 by Michael Knoedler, and had among his vast base of collectors clients such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre and Tate galleries in London. While it was under the direction of Michael Knoedler’s son Roland, the gallery had financial difficulties and was purchased by Armand Hammer in 1971 for $2.5 million. (To remind, Armand Hammer, a businessman, art collector and philanthropist donated the bulk of his collection to what has become UCLA’s Hammer Museum. His grandson Michael Hammer was the chairman of the Knoedler Gallery since inheriting it in 1991–whose son by the way, is actor Armie Hammer whom you might recall played the Winklevoss twins who sued Mark Zuckerberg in the movie Social Network.)

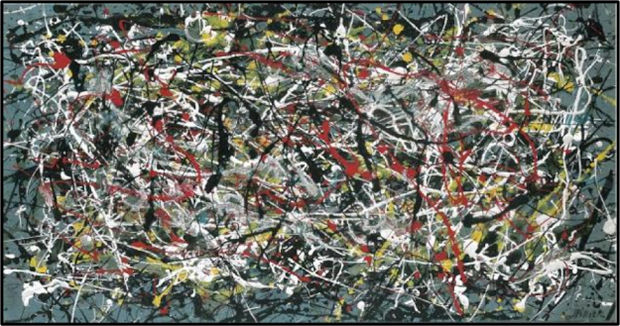

Now, on to what happened: The public heard of the closing of the Knoedler Gallery during 2011’s Art Basel Miami Beach after London-based Belgian hedge fund manager Pierre Lagrange filed a suit against the gallery for what turned out to be a fake Jackson Pollock he had purchased for $17 million. (The former director of the gallery Ann Freedman had left in 2009 and gone on to open her own gallery, again in New York in very close proximity to the Knoedler).

fake Pollock, painted by Pei-Shen Qian

Photo: Phaidon

What had happened was that between 1994 to 2008 Glafira Rosales, an art dealer from Long Island had approached the gallery’s director Ann Freedman about selling paintings from a private collection consisting of never-before-seen Abstract Expressionist paintings of Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollock among others. The collector located in Switzerland and traveling between Switzerland and Mexico, wanted to remain anonymous and was therefore called Mr. X. None of the artists’ catalogues raisonnés included any of the works available for sale from Mr. X’s collection.

Glafira Rosales

Photo: John Marshall Mantel for The New York Times

Still, the Knoedler Gallery, under the directorship of Ann Freedman bought the forged Modernist works and then went on to sell them to other buyers. Among them were a Rothko sold for $8.3 million in 2004 to Eleanore and Domenico de Sole, then-President and CEO of the Gucci group, now chairman of Sotheby’s and Tom Ford as well as the director of Gap, and a Willem de Kooning, sold to John D. Howard, the co-managing partner of the private equity firm, Irving Place Capital which used to be Bear Stearns Merchant Banking, for $4 million in 2011.

Ann Freedman

Photo: artfcity.com

In the end, they were all found to be fakes, done by a Chinese artist named Pei-Shen Qian living in Queens—who has long escaped and is presumed to be in China. He was commissioned the works by Glafira Rosales’ boyfriend of more than 30 years, José Carlos Bergantiños Díaz, with whom she has a daughter. Rosales has since pleaded guilty to charges of forgery, tax evasion and wire fraud among others, whereas José Carlos Bergantiños Díaz, a man who according to the Spanish press is an art lover with classy manners, and his brother Jesús Ángel Bergantiños Díaz to whose accounts in Spain millions of dollars were transferred, were arrested in Spain. As of this moment extradition talks for the brother is in the process but José Carlos Bergantiños Díaz is awaiting trial in Spain.

José Carlos Bergantiños Díaz

Photo: laregion.es

This has been the only case that made it to the court against Freedman and the Knoedler: Eleanore and Domenico de Sole sued the gallery and the director for selling the fake Rothko, which has since been settled after testimonies of Mark Rothko’s son Christopher Rothko, David Anfam, author of the Mark Rothko catalogue raisonné, MoMA conservator James Coddington and the plaintiffs as well as others. In an interview given to artnet, de Sole stated that after receiving the report of a forensic analyst he hired, which stated that the Rothko was a fake, he approached the Gallery saying “'Fine, if it's authentic, give me my $8.3 million back and I'll walk away. Now you can sell this authentic Rothko for more than twice as much, $18 million, or whatever and you can make a huge profit.' When they absolutely refused to do that I knew that, one, the Rothko was definitely a fake, and two, they knew for sure that it was a fake."

Untitled, the fake Rothko, painted by Pei-Shen Qian

From Kevin P. Ray’s presentation at the PAMM, I found out that of all the 10 suits against the Knoedler Gallery and its then-director Ann Freedman including this last Rothko case, six have settled out of court and the others are still continuing.

The Courtroom with the fake Rothko

Photo: http://illustratedcourtroom.blogspot.com

For example I learned that Modigliani and Giacometti are heavily forged. And throughout art history there have been many other cases; even Michelangelo did make “a Sleeping Cupid in the antique manner (and was) told by a proto-dealer to ‘distress’ it so as to sell it as an antique at a higher price", and,

is either a Leonardo da Vinci, or is a false attribution, or is a modern forgery.

And of course the most fascinating has always been of the Vermeers. There are only 36 known Vermeers in existence, and as a teenager I was fascinated to hear that Vermeer was forged—and that even Hermann Goering bought one. I found out that these were actually done by Han van Meegeren.

Forged Vermeer by Han van Meegeren, purchased by Goering.

Of course art by contemporary artists are less likely to be faked, even though their media are easier to replicate compared to old artworks. Artists, their studios and representatives can be easily approached for questions, as catalogues raisonnés are updated and recorded digitally with each new work. Because of digitization it is all the more difficult to pass fakes off as authentic and selling them.

I think there will always be people who want to con, and we will always have them in every society. But why do we like hearing, reading or watching about them? Art historian Alexander Nagel in his article The Copy and its Evil Twin explains that “(t)he emergence of art forgery presupposes a culture in which what matters above all is not the content a work of art transmits but the irreducible qualities that make this work an unrepeatable event. Eventually this conception of art would form the basis of a discipline called the History of Art, which devoted its energies to putting each artistic performance on a timeline, and to studying it as the product of an author and a historical moment.” A forgery tries to change history as we know it and we like reading about the forgery because for a while we get to be part of the excitement; someone with a talent but is not original in style per se, goes back in time tries to change historical records through manipulation and almost gets away with it despite the scrupulous eyes of the art cognoscenti.

I mean, if the chairman of Sotheby’s is taken in, how are we to escape? This gives us a sense of relief, a consolation: if He can be scammed, then we feel a little better if we are conned in small ways. It happens to just about everybody.

But what good does it serve—if any—in the end? Well, art critic Blake Gopnik wrote in his New York Times article In Praise of Art Forgeries, that having fakes is a good thing because this way, the incredible rise of prices in the art market stops. And that speculators, art investors who are in it also for the prestige, the show off and value as investment than the sole love and appreciation of art are hesitant to buy--compared to how easily they normally do--and the bubble deflates a little. And that perhaps museums, the public institutions who can provide access to many more can finally afford to purchase some of those works. Of course this was never the intention of the forgers and fakers, and of course all criminals should be punished, but something good can come out of this too and that it might perhaps benefit the greater public eventually.

--

Here are some BOOKS on fakes, forgeries and heists:

The Art Forger, by B. A. Shapiro, is a nice novel about an art forger and one of the still unresolved art museum heists: that of the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston when it was robbed back in 1990. I loved this book when I read it, because it has forgery, heist and takes dramatic license to tell of the life of a woman who cared about the arts and founded a museum.

Forged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age, by Jonathon Keats provides a history of art forgers very much like the presentation I listened to.

The Art of the Con: The Most Notorious Fakes, Frauds, and Forgeries in the Art, by Anthony M. Amore who is a former assistant director of the TSA and now head of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston.

Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art, by Lanes Salisbury and Aly Sujo, tells the story of how John Myatt did copies and John Drewe created documents to provide provenance for the works.

Priceless: How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World's Stolen Treasures, by Robert K. Wittman (Author), John Shiffma, tells the story of how Robert Wittman former FBI investigator, created the FBI’s Art Crime Team. The work he did uncovering scams while undercover are remarkable.

And FILMS:

Art and Craft, a documentary about Mark Landis who forged works and then went ahead and donated them to museums in a span of 30 years.

And for me, one great film, one that I have just watched once more being alone this year on Valentine’s Day, is the Thomas Crown Affair, with Rene Russo and Pierce Brosnan. Rene Russo is smart, beautiful, has a great haircut. While the film is about a museum heist--the Met--it also includes forgery as the characters try to find out about the authenticity of their love.

I kept thinking, I know this is a remake of the original back in 1968 with Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway—who is also present in this movie in the psychiatrist’s role—in which McQueen’s character robs a bank instead of a museum; that if this were movie to be made again today, would the Male protagonist, who would be in his 40s again, be partnered with a woman his age as it is in this one, or someone half his age? Would she have a beautiful body with normal proportions as Russo does or would she be all artificial as we are so acustomed to seeing all around us? Which makes me wonder: At this day and age, what is really real and authentic, when almost everything is fake or make-believe?

Comments